|

Technocracy: The Hard Road to World Order

By Patrick M. Wood Published in November 2018 234 Pages Thibault’s Score: 4/5 This is an absolutely fascinating read. It was written in 2018, and it is remarkably prescient. It perfectly anticipates the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Technocracy is a political movement that originated in the 1930s. The original technocracy movement advocated for the scientific management of the economy. The goal of the technocrats was to create a centrally planned economy that would be managed by engineers using scientific data. By the time of World War Two, the technocracy movement petered out. However, many of its ideas would be adopted by the economic planners of FDR’s New Deal and of the wartime economy. This book traces how the obscure technocracy movement from the 1930s influenced modern political thinking, especially when it comes to global organizations such as United Nations, the World Economic Forum, the WTO, etc… Many current political and economic developments are no longer being primarily driven by the nation state. Now, most policy is being driven by a loose network of international para-governmental organizations (such as the UN), think tanks (such as the Brookings Institution), NGOs (such as the World Wildlife Fund), and consulting firms (such as McKinsey and Company). Democracy and traditional means of restricting governments are being bypassed using a wide variety of complicated mechanisms, the end result being the global homogenization of all legal and regulatory mechanisms. This book does a great job of explaining why governments no longer are responsible for policy making, and what ideas are driving this trend. I have one major criticism: the author is very critical of technocracy. As a result, he doesn’t do a very good job of explaining the pros of technocracy, only the cons. He comes from a conservative American Christian background, and doesn’t hesitate to use words such as “un-American” to describe various ideas and policies. Although his research is very good, and his findings align with things that I have seen in my professional life, his tone will be repulsive to the overwhelming majority of readers. As a result, his credibility suffers, and this book cannot be shared with the majority of people that I know. I wish that he had written a calm, collected, and unbiased book about technocracy. On one hand, I can find books that support technocracy. These accounts always use euphemisms and besmirch opponents as conspiracy theorists. On the other hand, I can find conservative or communist critics who are obviously biased. What I cannot find are neutral accounts that eschew euphemisms but simultaneously (at least on the surface) appear neutral. This is the best that I have found so far, so I will probably recommend it to a limited number of friends with many caveats.

0 Comments

Useful Enemies: Islam and The Ottoman Empire in Western Political Thought, 1450-1750

By Noel Malcolm Published in 2019 512 Pages Thibault’s Score: 2/5 I only made it about a quarter of the way through this book before I decided to put it down. Malcolm’s main argument is that, by the mid 1600s, the Ottomans had become a pathetic shadow of their former selves. They no longer posed any real threat to Europe. However, European states found the threat of the Ottomans to be useful. Defense against the Ottomans justified religious persecution, raising taxes, military expenditure, etc… The Europeans would go as far as intentionally propping up the Ottomans in order to keep their threat alive. There is a lot of stuff out there about the rise of the Ottoman Empire, the conquest of Constantinople, the Balkan and Habsburg wars, and the age of Suleyman the Magnificent. There is perhaps even more stuff out there about the fall of the Ottoman Empire. However, there are very few books about the long boring period after the rise of the Ottoman Empire but before its decline. I was looking for a history of the Ottoman Empire during the late 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, so I picked up this book. This book doesn’t discuss the history of the Ottoman Empire, but rather European perceptions of the Ottomans. Like most modern historical works, it overemphasizes bias and under emphasizes understanding. The tone of writing is academic. I could see a potential audience for this book, but it wasn’t for me. The Enemy at the Gates: Habsburgs, Ottomans, and the Battle for Europe

By Andrew Wheatcroft Published in November 2010 384 Pages Thibault’s Score: 3/5 This book is a fairly standard narrative history describing the two Ottoman attempts at capturing Habsburg Vienna in 1529 and 1683. It opens by highlighting the local geographical politics. Then, it gives broad explanations of the Austrian and Ottoman armies and tactics. Most of the book concerns direct hour by hour descriptions of the various battles and conflicts. Finally, some were devoted to the aftermath. Although the book was fast paced and the descriptions of battles were interesting, I remember remarkably little. You can only read about so many cavalry charges, famines, and last stands before it all starts to blur into one. The writing style was great, and at the moment, I found the book very interesting. But endless accounts of battles inevitably become drab. I never feel like I learn a lot when I read military history. Military history rarely gives me insight into the evolution of societies, the reasons why things are the way that they are, or the lives of people who lived in the past. Although it's a good book, unless you are specifically studying either the Habsburgs or the Ottoman Empire, there probably isn’t any good reason to pick up this book. UFOs: Generals, Pilots, and Government Officials Go on the Record

By Leslie Kean Published in August 2011 352 Pages Thibault’s Score: 4/5 This was an extremely strange book. This book is a compilation of interviews with various retired high level government and military officials talking about their experiences with UFOs. The forward was written by Hillary Clinton’s chief of staff John Podesta. Whether or not the human race has made contact with extraterrestrials remains to be seen. However, it seems completely incontrovertible to me that high level military, government, and intelligence officials believe that earth has made contact with extraterrestrials. Most of the witnesses of UFOs interviewed in this book are military pilots and ground control staff. Almost all of the encounters described in this book were captured on various equipment (radio, sonar, camera, radar, etc…); and aren’t just eyewitness accounts. What is fascinating is that the officials who witness these various UFOs do not immediately assume it is simply a complicated or unusual weather phenomena or top secret technology from other states; but instead assume that they are extra terrestrial. If you are looking for a good introduction into the question of UFOs, then I would recommend this book as a good starting place. The Sultan and the Queen: The Untold Story of Elizabeth and Islam

By Jerry Brotton Published in September 2016 338 Pages Thibault’s Score: 5/5 On its face, this book is a history of late medieval England’s relationship with the Ottoman Empire. However, when you dig deeper, it is much more than that. It is actually the history of the beginnings of international trade, global empire, and of a multicultural England. I’m not a big fan of the writing style. I think that the style suffers from academic pedantry, although it isn’t too bad. The writing style isn’t exceptionally clear or concise, but it isn’t bad either. The book covers a wide variety of different contacts in-between Elizabethan England and the Ottomans - military, artistic, and most importantly commercial. It immediately becomes very clear that by the 1500s, England and the Ottoman Empire were much more closely connected than the average person would imagine. The first, and most obvious, connection in between England and the Ottoman Empire is geopolitical. The two shared a common enemy: the Habsburg Holy Roman Empire. Previously, the Ottomans had briefly allied with another Habsburg enemy: France. The Ottomans had a history of alliances with various Christian powers such as Wallachian, Byzantium, Venice, and many others. In 1500, the European country with the largest population of Christians was the Ottoman Empire. From the English perspective, Islam was foreign; but from the Ottoman perspective, Christianity was well understood. Although geopolitics was the main initial driver of Elizabethan and Ottoman relations, it would have - by far - the smallest impact. Within decades of geopolitical contact, trade flourished. Many Englishmen found themselves in the Ottoman Empire; and many Ottomans in England. Very quickly, Turks become a staple of pop culture. The book goes on - at length - about how the Ottomans appear in fictional books, songs, and plays. Even the great Shakespeare writes extensively about Ottomans in plays such as “The Merchant of Venice” and “Othello.” Although I found this to be, by far, the least interesting part of the book, it still managed to captivate me. Finally, the most important connection between England and the Ottoman Empire is through trade. This trade will lay the foundation for later British colonialism. It begins with something I had never heard of: the English state-owned Muscovy company, which was created to attempt to access Middle Eastern markets through Russia. Although trade through Russia would prove ruinously expensive, the nature of state-owned trading companies (as opposed to more market driven initiatives as existed in Italy) would become the bedrock of colonialism. This book details fascinating encounters and adventures involving British merchants in Persia, the Indian Ocean, Russia, Crimea, Morocco, and sub-Saharan Africa. The stories of the brave merchants, who opened the world, is ultimately why I gave this book a five. I recommend reading this book to understand how trade opened up Europe. The King in Yellow

By Robert W. Chambers Published in 1895 160 Pages Thibault’s Score: 2/5 The King in Yellow is a collection of short stories written in the late 19th century by American author Robert Chambers. I bought the book for three reasons. First, it was a favorite of HP Lovecraft, who is an author who influenced me. Second, I physically liked the book (it's beautifully printed, pictured is my copy). Finally, I wanted to have some short stories that I could quietly read (not audiobook) while my daughter sleeps. I was hoping for some Lovecraftian cosmic horror. Instead, I got some mediocre sappy 19th century romantic fiction mixed in with discount Edgar Allan Poe tier spooky fiction. Because I don’t recommend it, this review will contain spoilers. The first story that I read, called The Repairer of Reputations, had an extremely interesting set up. It takes place in New York in 1920. Of course, because the book was written in 1895, it isn’t our 1920 - its 1920 as it was imagined by an American upper-class elite author from 1895. The story correctly predicts WW1, the militarization of America, the exclusion of Jews from immigrating to the US, and the redevelopment of New York city. It also makes some seemingly absurd predictions such as the creation of an independent negro state in Louisiana. I got a great dystopian vibes from it. However, the rest of the story fell flat. I then read a mediocre soppy romance story about two sculptors who loved the same French woman, and a boring lazy story about some guy who fell asleep during mass at a church and had a nightmare. Finally, the last story was about a painter who saw a creepy man staring at him from the window. It was a little bit more mysterious than the other three stories, and had some better Lovecraftian elements; however it still fell short. Overall I do not recommend the King in Yellow. Four Princes: Henry VIII, Francis I, Charles V, Suleiman the Magnificent and the Obsessions that Forged Modern Europe

By John Julius Norwich Published in April 2017 304 Pages Thibault’s Score: 3/5 During the Middle Ages, Europe was divided into a cacophony of small feudal land holdings and city states. As gunpowder technology made the destruction of castles easier, large territorial states began emerging in Western Europe for the first time since the collapse of the Frankish empire. These large states were characterized by a new class of posh, style-obsessed, arrogant elites. Four prices who are emblematic of their era - Henry VIII of England, Francis I of France, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, and Sultan Suleiman all coexisted and interacted. All of them come off as horrible power-obsessed human beings, who care little for either their own people or morality. None were looking out for the good of their people; all were instead focused on their own careers and families. Out of these four, the only exception being Charles V, who was a genuinely pious monarch. This book isn’t extremely interesting, but it gives some insight into a time of scheming and political trickery. What is interesting to me is that during the Middle Ages, these schemes took place but didn’t affect nearly as many people. Average, everyday people could safely ignore the plots and delusions of their rulers. The power of the state was so weak, governments were so localized, and wars were so small-scale that normal people could ignore politics. However, the early modern era was a very different time. This was the time of totalitarianism and state-control of society. As a result, ordinary people suddenly found themselves at the whims of their elites. I don’t recommend this book. It is very similar to a similar book that I recently read called Defenders of the Faith which is much better. Great Siege: Malta 1565

By Ernle Bradford Published in January 1961 256 Pages Thibault’s Score: 4/5 This book is an early 1960s pop history account of the siege of Malta. The book was written by WW2 British veteran Ernle Bradford. Later, he spent 30 years sailing across the Mediterranean, and studying the history of naval warfare and maritime trade. As a result, this book is way more interesting than if it had been written by some historian who never accomplished anything in the real world. The book is a fast-paced hour by hour account of the mind-blowingly epic siege of Malta. This battle constitutes Christianity’s most epic stand against Islam. A small group of Catholic knights defeated an Ottoman army roughly twenty times larger than their garrison, stopping the Turkish advance. Had the knights lost the siege of Malta, the Ottomans would have likely been able to invade Spain and Sicily. Instead, it marked the second major Ottoman defeat after the earlier failed attempted siege of Vienna. The knights were a group of old crusaders who had been forced to abandon their last Eastern outpost on the island of Rhodes several decades earlier after the Ottomans successfully captured it. They came from a variety of backgrounds - French, German, Spanish, English, etc… Assisting them was a group of ragtag Maltese Catholic peasants who hated the knights. The Maltese, although Catholic, spoke a dialect of Arabic and prayed to a God they called “Allah” (albeit in Catholic masses). The crusaders were able to win the siege thanks to the charismatic leadership of 70 year old Hospitaler grandmaster Jean Parisot de Valette. He was able to unite the fragmented Catholic forces, and crush the Ottoman attack - despite getting almost no outside assistance. This is one of the most epic battles in history, and this book does it justice. If you want to read a fast-paced historical account of a battle, this is the book for you. UFOs and the National Security State: Chronology of a Coverup 1941 - 1973 (Vol 1)

By Richard M. Dolan Published in June 2002 478 Pages (Volume 1) Thibault’s Score: 5/5 Note - I only read volume 1 of 2. I cannot find an audiobook for volume 2, and only have a physical copy. I currently have no plans to read volume 2, and am saving it for a rainy day. This is, by far, the best book that I have read about UFOs / extraterrestrials visiting earth. The UFO / UAP phenomenon is very hard to document. However, the US government’s coverup of UFOs is as clear as day. This book isn’t about UFOs per say but rather about the US government’s response to UFOs. I liked many aspects of this book. First, it doesn’t make any outlandish claims. Instead, it sticks to events that can be well documented. Many of the UFOs described in this book were filmed, caught on radar, detected via sonar, and were otherwise documented on instrumentation. This book doesn’t also jump to the conclusion that UFOs are aliens. Instead, it explores many other possibilities such as weather phenomenon or secret aerial craft developed by the US government. It is also incredibly well researched. The physical copy contains about 100 pages of citations and footnotes about the history and authenticity of each citation. In the 1950s and 1960s, many scientists, army officers, and other credible investigators who looked into UFOs / UAPs found that their careers fell apart. Later, many high level intelligence and army officers testified that they had been assigned to destroy the lives of government officials investigating these phenomena. Outsiders can only speculate about why the army and US intelligence agencies were so interested in stifling investigation of UFOs. This book avoids speculating too much, instead sticking to the facts. Here are five key takeaways: -Many UFO / UAP sightings have significant non-witness data (radar data, sonar, etc…) as well as an eyewitness component -Many encounters have resulted in airplane crashes, the death of military personnel, and other incidents -Western / NATO governments have systematically attempted to stifle the evidence of UFOs -More credible encounters tend to report lights in the sky and strange aircraft. Less credible encounters report little green men, abductions, etc… -Western intelligence agencies have directed the media to ignore credible encounters and promote sensational / crazy encounters If you want to seriously dive into UFOs / UAPs / aliens, this is the book where I would start. The Day After Roswell

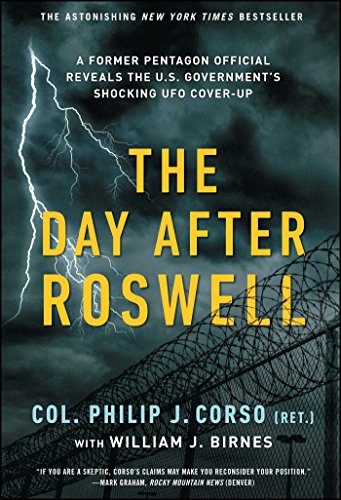

By Philip Corso Published in June 1998 384 Pages Thibault’s Score: 1/5 Philip J. Corso was a retired and decorated military officer who served in Roswell in the years after the crash. When I found out he had written an extremely detailed account of the Roswell incident, which he published posthumously, I was very excited. He seemed credible. This book is not a factual account of any real events. Instead, it is a mediocre science fiction novel with only the thinnest pretense of reality. It is an overly dramatic History-channel tier book that is written in the style of an action adventure novel. Instead of carefully explaining his sources, laying out his evidence, assessing the honesty of different witnesses, and making a strong case Corso immediately starts with these dramatic accounts of little green men. I stopped reading after the third chapter. This book is a complete waste of time for any serious readers. Only the most naive dupes can believe anything here. If you want to read good books about potential contact with extraterrestrials, they are out there - but this isn’t it. Likewise, if you want to read high quality sci-fi, this isn’t it either. |

Thibault SerletMost of my articles are book reviews, but I also write about many other topics. Archives

December 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed